Marriage and the Principle of Guilt

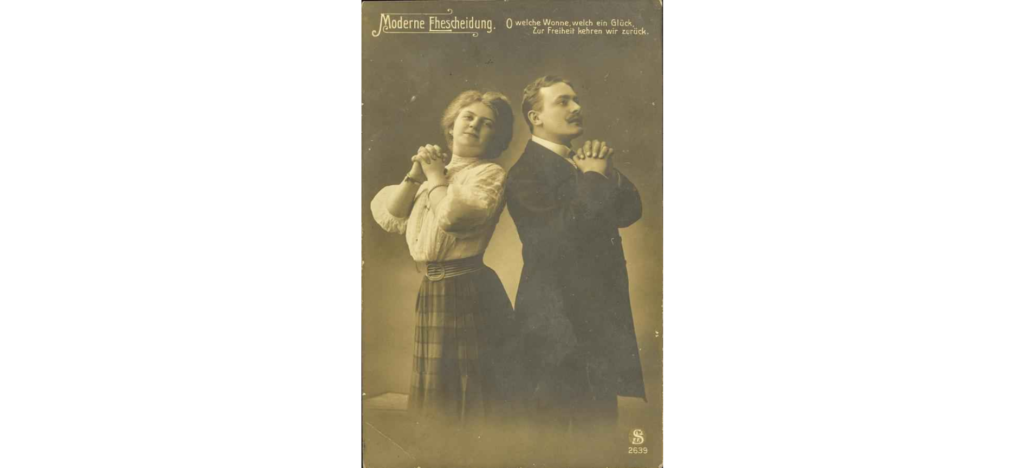

In the Weimar Republic, there was a heated discussion about amending the laws regarding marriage and divorce. Because the Christian understanding was that marriage was a lifelong commitment, the 1900 Civil Code (BGB) only permitted divorce on serious grounds including adultery, danger to life, malicious desertion, violation of marital duties, and insanity.

Marriage and the Principle of Guilt

In the Weimar Republic, there was a heated discussion about amending the laws regarding marriage and divorce. Because the Christian understanding was that marriage was a lifelong commitment, the 1900 Civil Code (BGB) only permitted divorce on serious grounds including adultery, danger to life, malicious desertion, violation of marital duties, and insanity.

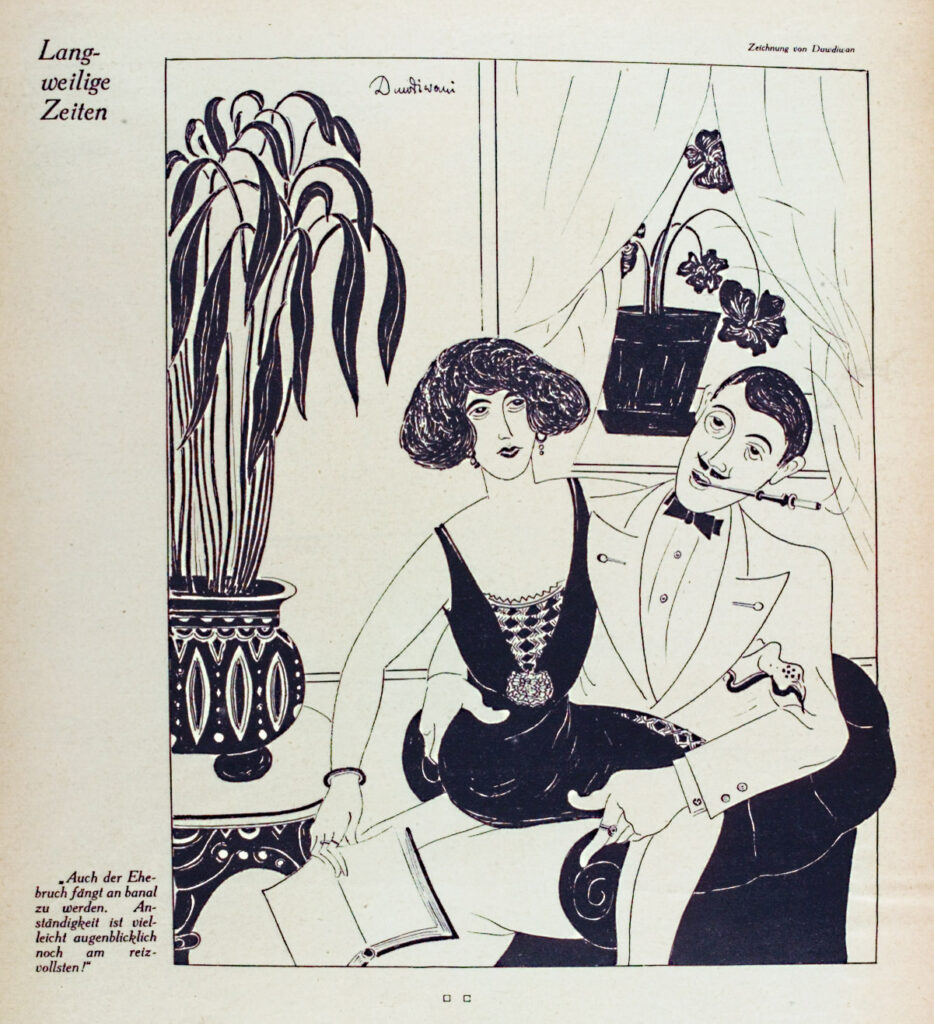

In the case of divorce, a judge would assign the blame to one of the partners, who would then be unable to assert any financial claims against their former spouse and often lost access to children. This arrangement often caused financial problems for women, many of whom were not employed at the time.

It was not until 1938 that a Marriage Act was passed in which the principle of guilt was included.

In the GDR (as of 1955), a marriage could be divorced if the court held that the marriage had lost its meaning for the married couple, the children, or society. In the BRD, the breakdown principle legally replaced the fault principle in 1976.

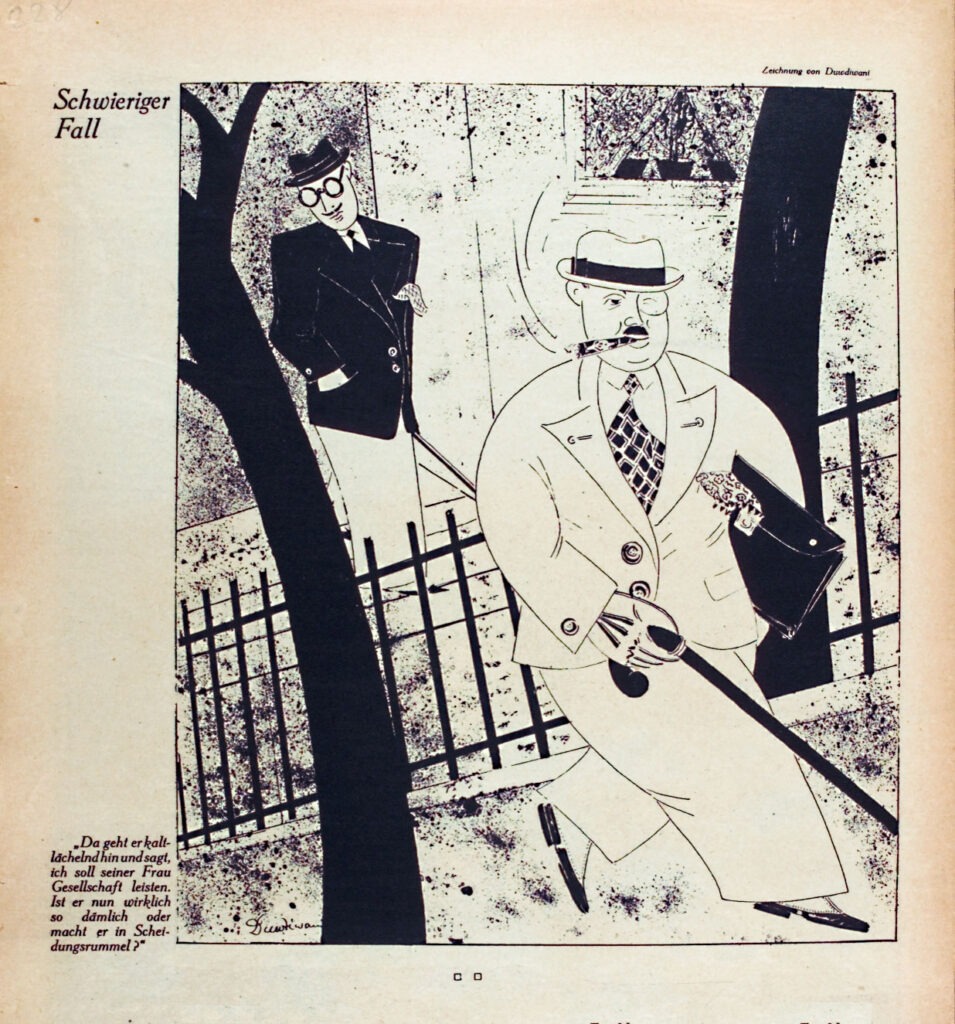

A Difficult Case

“There he goes, telling me to keep his wife company. Is he stupid, or is he trying to get divorced?”

A man wonders if the request of a husband to visit his wife is merely “stupid” or a deliberate attempt to provoke adultery. According to the divorce law at the time, adultery would have released the husband from the financial claims of his wife.

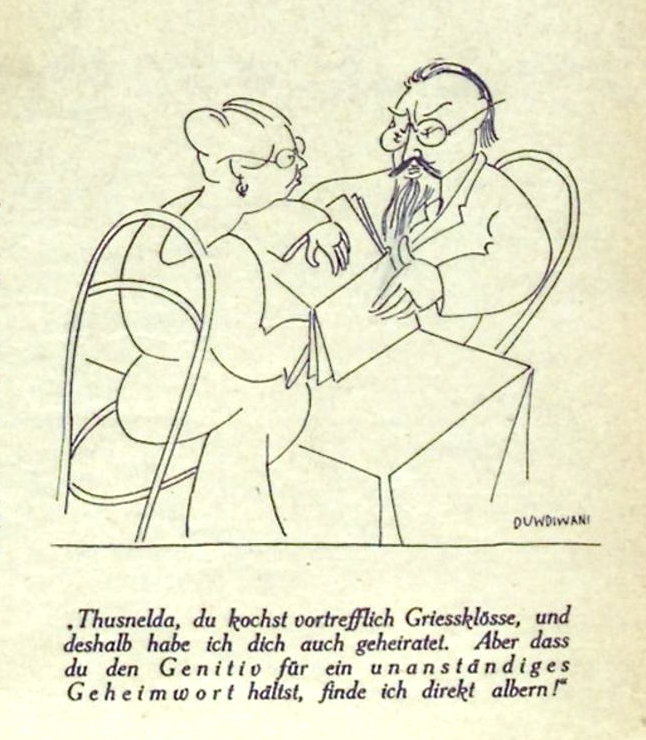

Kochkünste

»Thusnelda, du kochst vortrefflich Griessklösse, und deshalb habe ich dich auch geheiratet. Aber dass du den Genitiv für ein unanständiges Geheimwort hältst, finde ich direkt albern!«

Die Karikatur beschreibt die Rollenzuweisung der Frau, die offensichtlich nur wegen ihrer Kochkünste geheiratet wurde. Angesichts ihrer mangelnden Sprachkompetenz deutet sich nun allerdings eine Zerrüttung der Ehe an.

Dirk Blasius: Ehescheidung in Deutschland 1794–1945. Scheidung und Scheidungsrecht in historischer Perspektive (= Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft Bd. 74). Göttingen 1987.

Thorsten Eitz: »Ehe oder Hölle?« Der Diskurs über Ehe, Eherecht und Partnerschaftsethik. In: Ders. / Isabelle Engelhardt: Diskursgeschichte in der Weimarer Republik Bd. 2, Hildesheim/Zürich/New York 2015, S. 164–219.

Michael Humphrey: Die Weimarer Reformdiskussion über das Ehescheidungsrecht und das Zerrüttungsprinzip. Eine Untersuchung über die Entwicklung des Ehescheidungsrechts in Deutschland von der Reformation bis zur Gegenwart unter Berücksichtigung rechtsvergleichender Aspekte. Göttingen 2006.