Art and artist

Kirszenbaum’s artistic work includes both representative descriptions and works influenced by Expressionism. In the early 20th century, the Expressionists were concerned with the expression of subjective feelings, and in doing so they resolutely opposed the Naturalists and Impressionists. The Bauhaus manifesto of April 1919, written by Walter Gropius (1883–1969), explicitly turned against the “old art schools” that had lost themselves “in salon art”.

Art and artist

Kirszenbaum’s artistic work includes both representative descriptions and works influenced by Expressionism. In the early 20th century, the Expressionists were concerned with the expression of subjective feelings, and in doing so they resolutely opposed the Naturalists and Impressionists. The Bauhaus manifesto of April 1919, written by Walter Gropius (1883–1969), explicitly turned against the “old art schools” that had lost themselves “in salon art”.

As Duwdiwani, Kirszenbaum liked to mock fellow artists and himself in his caricatures.

Optical confusion

“Strange, dear friend, your model is very slim, while the lady in the picture is bursting at the seams. I think you need to get some glasses!”

Duwdiwani had obviously encountered cases with artists who adhered to a naturalistic style of painting in which the pictures deviated significantly from what was to be depicted. In the caricature, the painter had captured an actually slender model, quite corpulent, on the canvas.

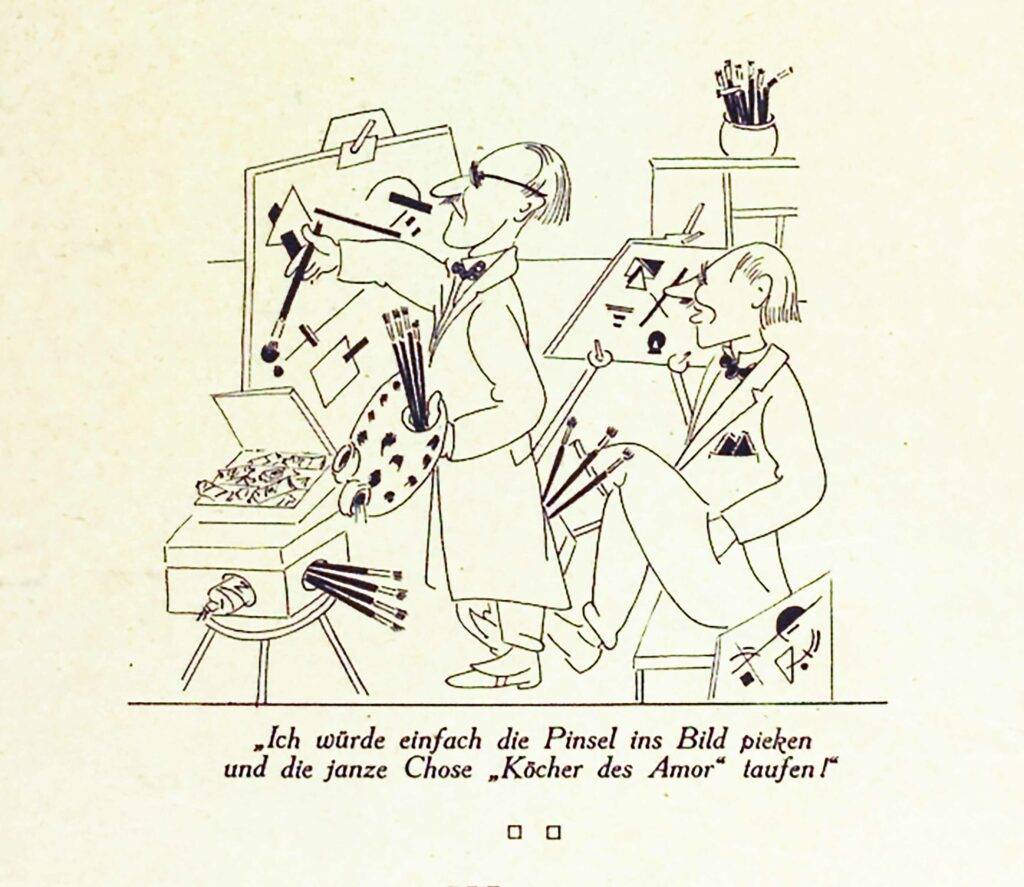

Expressionist painting

“I would simply poke the brushes into the picture and then christen the whole painting ‘Cupid’s Quiver.’”

The goal of an expressionist painter was to give the viewer a unique experience through the aggressive deformation of natural forms and structures. According to the experience of Duwdiwani, sometimes artists would put the intended artistic statement of the artwork in a title. The works depicted in this cartoon are similar to the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), who had been a teacher at the Bauhaus.

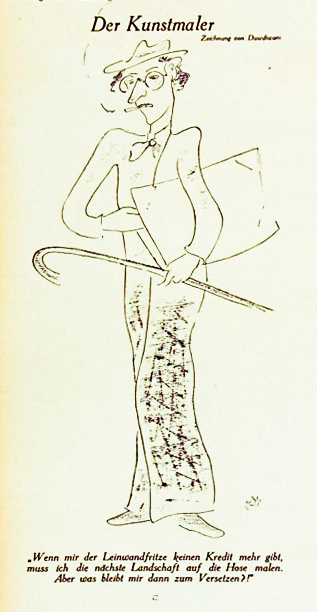

The painter

“If the canvas guy won’t give me any more credit, I’ll have to paint the next landscape on my pants. But will be left for me to pawn?”

Perhaps Duwdiwani uses this cartoon to reflect on his own economic situation. Many artists feared that they would soon have to paint on their only pants because they could not afford a canvas.

Multiple Talents

“I have something Orange in mind. This transposed into the atonal would result in a phenomenal six-liner.”

In one of Duwdiwani’s first cartoon for ULK in 1926, an artist strives to combine art, music, and poetry in an expressionist symbiosis. This could be a reference to Duwdiwani’s Bauhaus teacher Paul Klee (1879–1940), who painted “Fugue in Red” and wrote poems simultaneously in 1921. Bauhaus master Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) also experimented with the interplay of painting and music.

Ulrike Ackermann / Ulrike Bestgen (Hg.): Das Bauhaus kommt aus Weimar. Katalog zur Ausstellung. Weimar 2009.

Magdalena Droste: Bauhaus. Aktualisierte Ausgabe. Köln 2019.

Peter Hahn (Hg.): Bauhaus Berlin. Auflösung Dessau 1932. Schließung Berlin 1933. Bauhäusler und Drittes Reich. Eine Dokumentation zusammengest. vom Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Weingarten 1985.

Bernd Hüttner / Georg Leidenberger (Hg.): 100 Jahre Bauhaus. Vielfalt, Konflikt und Wirkung. Berlin 2019.

Winfried Nerdinger: Das Bauhaus. Werkstatt der Moderne. München 2018.

Paulina Olszewska: Lass uns feiern! Feste am Bauhaus. Hg. vom Goethe-Institut Polen in der Reihe »Die ganze Welt ein Bauhaus?« 2020

Online: https://www.goethe.de/ins/pl/de/kul/mag/21793573.html

Michael Siebenbrodt / Lutz Schöbe: Bauhaus 1919 – 1933. New York 2009.

Frank Simon-Ritz/Klaus-Jürgen Winkler/Gerd Zimmermann (Hg.): Aber wir sind! Wir wollen! Und wir schaffen! Von der Großherzoglichen Kunstschule zur Bauhaus-Universität. 1860–2010. Band 1 (1860–1945). Weimar 2010, S. 147–243.