“The Blue Angel”

The term “New Woman” was used at the end of the 1900s to describe the growing number of educated and independent women in Europe and the United States who emerged first during the first women’s movement. In the 1920s, cultural centers such as Berlin and Munich saw an evolution of the “New Women”, also sometimes referred to as a “flapper”.

The “New Woman” of the 1920s

The term “New Woman” was used at the end of the 1900s to describe the growing number of educated and independent women in Europe and the United States who emerged first during the first women’s movement. In the 1920s, cultural centers such as Berlin and Munich saw an evolution of the “New Women”, also sometimes referred to as a “flapper”.

“Flappers” went against social conventions by wearing shorter and tighter skirts, having short hair, drinking alcohol, smoking in public, and wearing makeup – which previously only prostitutes and actresses did. Marlene Dietrich (1901–1992) was viewed as an icon for flappers.

The Great Depression and the image of women imposed by the Nazis put an end to the attempt at modernizing the female identity and role.

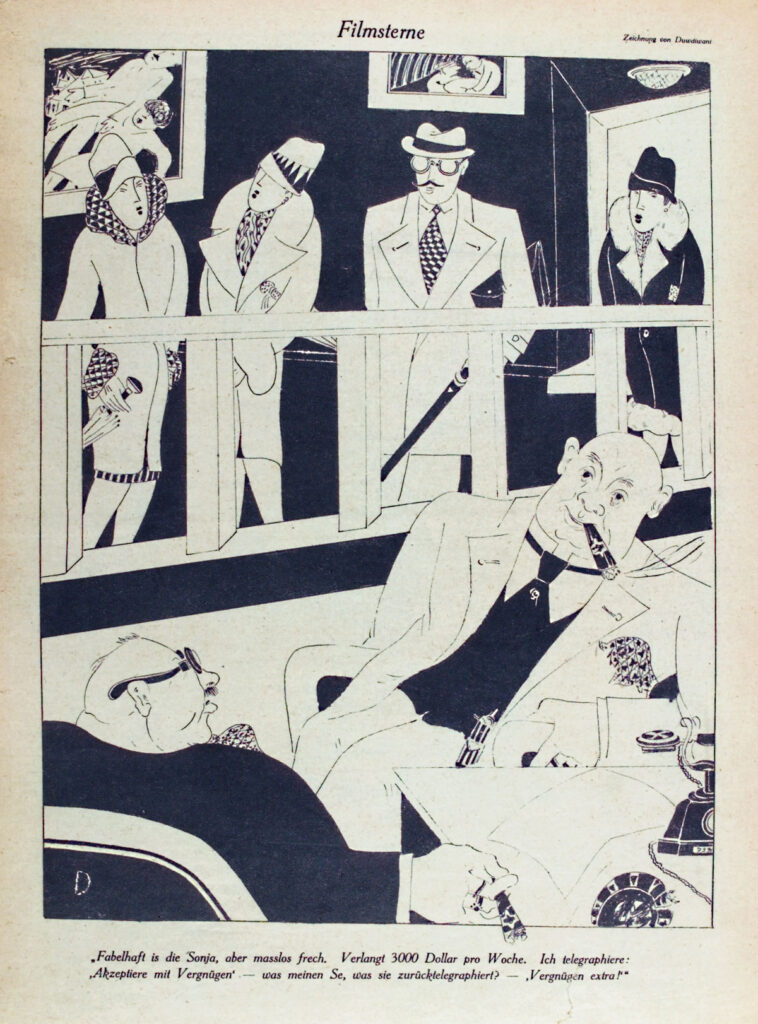

Filmstars

“Sonja is fabulous but very cheeky. Demands 3000 dollars per week. I telegraphed ‘accept with pleasure’ – what does she mean by responding ‘pleasure is extra!’”

Female film stars were among the top earners in the Weimar Republic. In the entertainment industry, an unusual liberalism and sexual freedom emerged, which caused anxiety in conservative circles.

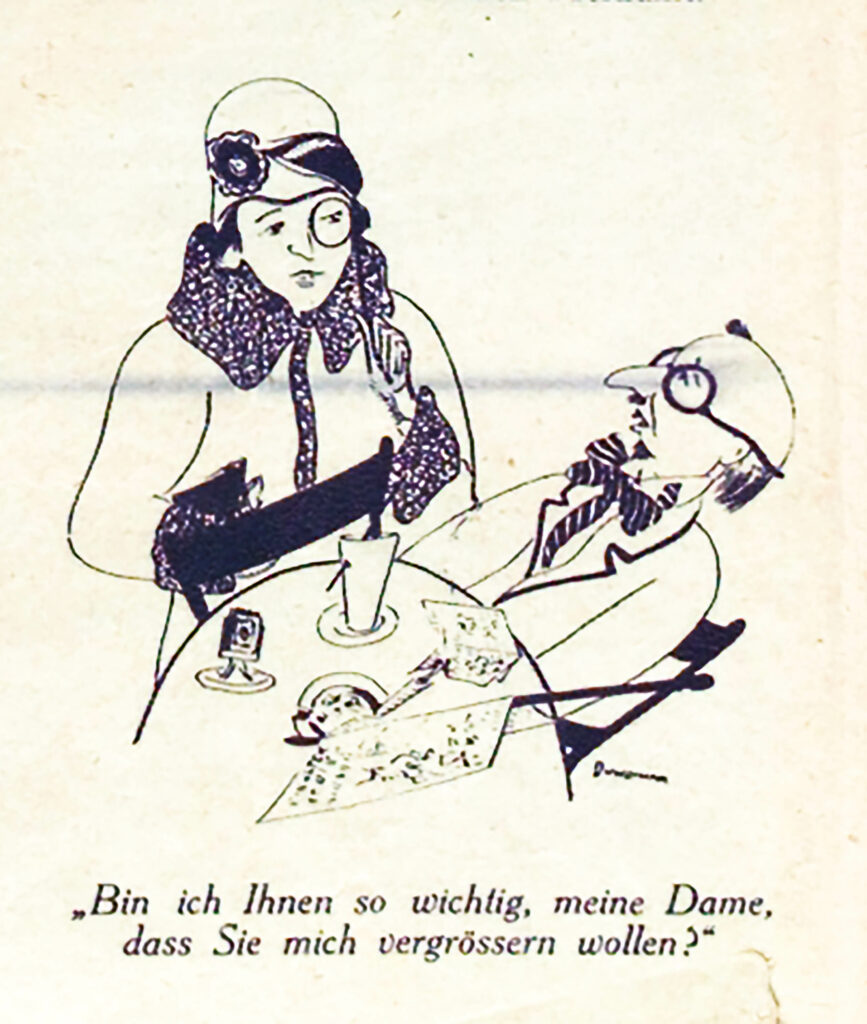

Insecurity

“Am I so important to you, my lady, that you wish to make me bigger?”

In this caricature, a man feels insecure as his wife critically looks at him through a monocle. Until the end of the First World War, the monocle was a popular status symbol for wealthy men and officers. The monocle was also an accessory used to identify oneself as protagonist for the “New Woman” of the Weimar Republic.

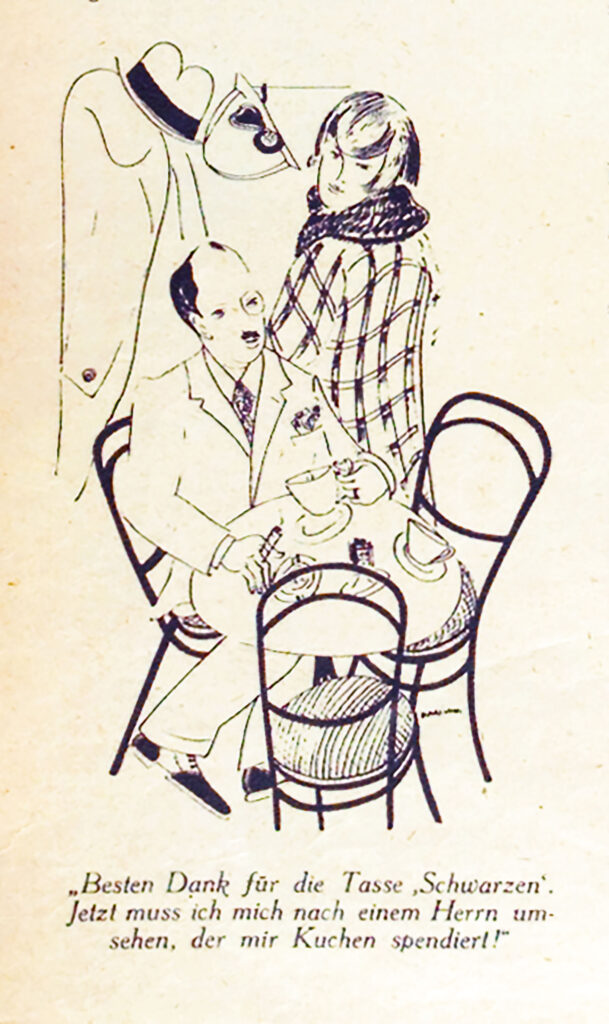

Expendable Men

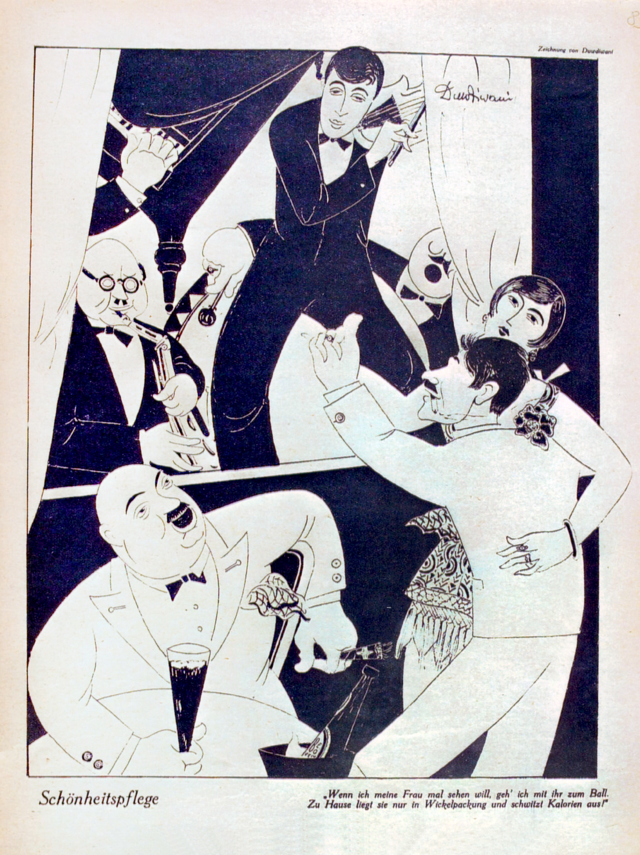

Beauty care

“If I want to see my wife, I’ll just go with her to the ball. At home she just lies around wrapped up in a body wrap sweating out calories.”

Because the fashion at the time dictated that women in their twenties should be thin, the wife of this gentleman is very busy trying to lose weight.

Frank Becker: Die Sportlerin als Vorbild der »neuen Frau«. In: Sozial- und Zeitgeschichte des Sports 8 (1994), H. 3, S. 34–55.

Julia Bertschik: Weibliche Pioniere. Neusachliche Frauentypen zwischen Wunschtraum und Selbstreklame in der Literatur der Weimarer Republik. In: Der Deutschunterricht 2006, H. 4, S. 5–13.

Marieluise Fleißer: Eine Zierde für den Verein. Roman vom Rauchen, Sporteln, Lieben und Verkaufen. In: Dies.: Gesammelte Werke, Bd. 2, Frankfurt a. M. 1994, S. 7–204.

Julia Haungs: Die »Neue Frau« der 1920er. Träume vom selbstbestimmten Leben. Manuskript der Sendung KULTUR NEU ENTDECKEN von SWR2 am 8. Oktober 2020.

Online: www.swr.de/swr2/wissen/die-neue-frau-der-1920er-traeume-vom-selbstbestimmten-leben-swr2-wissen-2020-10-08-102.html

Kirsten Heinsohn: Frauenbewegung in der Weimarer Republik. Digitales Hamburg Geschichtsbuch.

Online: https://geschichtsbuch.hamburg.de/epochen/weimarer-republik/frauen-in-der-weimarer-republik/

Susanne Herzog; Die Neue Frau. In: Die Weimarer Republik. Lebendiges Museum Online 2014. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin.

Online: https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/weimarer-republik/alltagsleben/die-neue-frau.html

Kai Nowak: Projektionen der Moral. Filmskandale in der Weimarer Republik (= Medien und Gesellschaftswandel im 20. Jahrhundert; Bd. 5). Göttingen 2015.

Patrick Rössler: »Es kommt … die neue Frau!« Visualisierung von Weiblichkeit in deutschen Printmedien des 20. Jahrhunderts – ein Bildatlas. Katalog zur Ausstellung der Universität Erfurt 2019.

Sylvia Schraut: Angekommen im demokratisierten »Männerstaat«? Weibliche Geschichte(n) in der Weimarer Republik. In: Ariadne. Forum für Frauen- und Geschlechtergeschichte Heft 73–74 / 2018, S. 8–18.