Devil Alcohol

Hyperinflation, unemployment, and high taxes on brandy in the Weimar Republic led to a significant decline in alcohol consumption compared to the 19th Century. Regardless, there was a significant movement against alcohol in the Weimar Republic. In 1921, teetotalers, who wanted alcohol completely banned, and temperenzers, who advocated for “sensible” consumption, jointly founded the Deutsche Reichshauptstelle gegen den Alkoholismus (German Reich Head Office Against Alcoholism) in Berlin.

Devil Alcohol

Hyperinflation, unemployment, and high taxes on brandy in the Weimar Republic led to a significant decline in alcohol consumption compared to the 19th Century. Regardless, there was a significant movement against alcohol in the Weimar Republic. In 1921, teetotalers, who wanted alcohol completely banned, and temperenzers, who advocated for “sensible” consumption, jointly founded the Deutsche Reichshauptstelle gegen den Alkoholismus (German Reich Head Office Against Alcoholism) in Berlin.

Church associations were allied with parts of the labor movement on this issue; however, many legislative initiatives designed to ban alcohol failed due to opposition from economic liberals, right-wing conservatives, and the government’s reluctance to give up tax revenues from spirits.

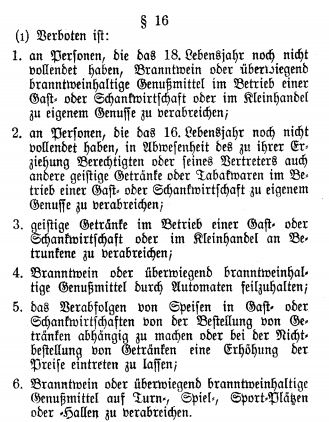

Finally, on April 28, 1930, the Reichstag passed a “hospitality law.” This law only banned serving alcohol to young people and spirits on soccer fields, but it at least reduced the income clubs gained from serving beer.

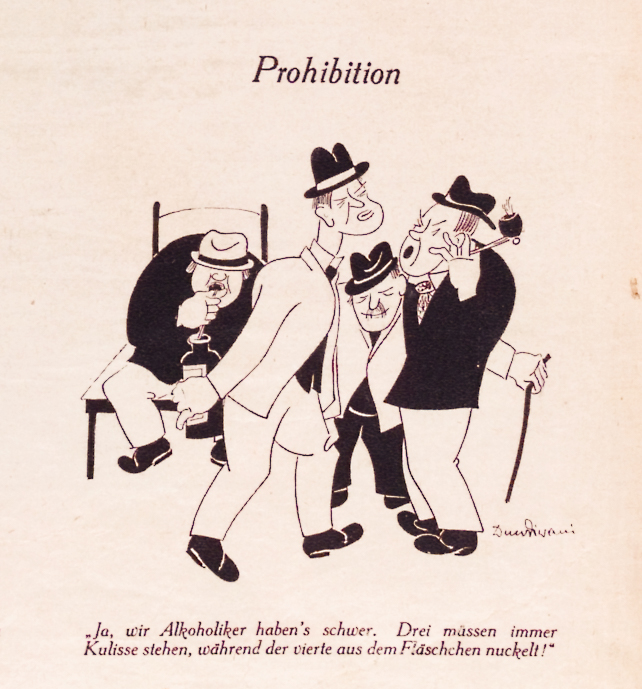

Prohibition

“Yes, we alcoholics have it tough. Three always have to stand guard while the fourth drinks from the flask!”

In 1926, when a law to prohibit alcohol was once again being discussed, Duwdiwani caricatured the precautions that drinkers might have to take in the future.

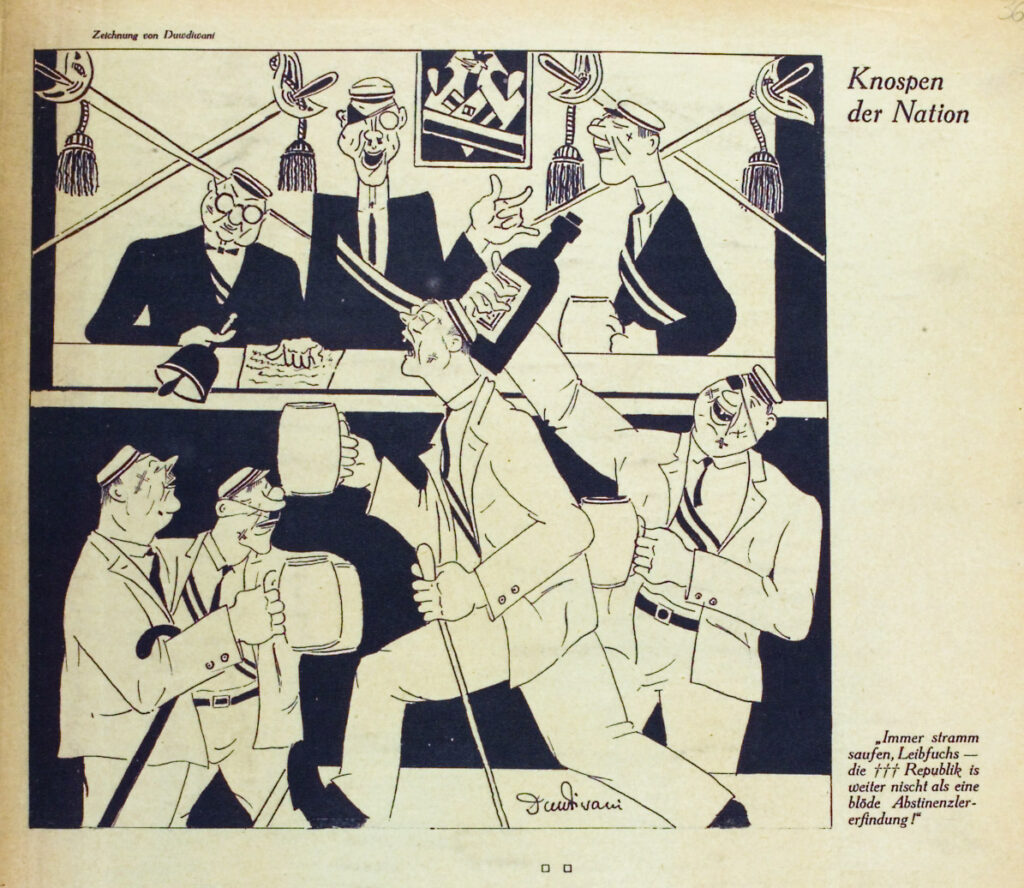

Buds of the nation

“Always drink hard, Leibfuchs – the Ɨ Ɨ Ɨ Republic is nothing more than a stupid abstinence invention.”

“Leibfuchs” is a first year who is to be prepared for full membership in a fraternity by working as a bellboy for three semesters. Here, a mentor explains to his protégé that the Weimar Republic was ultimately just an invention of the teetotalers.

Heinz Amberger (Hg.): Burschenschaftliches Arbeitsbuch. Frankfurt a. M. 1955. Artikel: »Der Leibbursch. Fuchs und Bursch«, S. 15–18.

Michael Grüttner: Alkoholkonsum in der Arbeiterschaft 1871–1939. In: Toni Pierenkemper (Hg.): Haushalt und Verbrauch in historischer Perspektive. Zum Wandel des privaten Verbrauchs in Deutschland im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. St. Katharinen 1987, S. 229–273.

Hasso Spode: Die Macht der Trunkenheit. Kultur und Sozialgeschichte des Alkohols in Deutschland. Berlin 1993.

Claudius Torp: Konsum und Politik in der Weimarer Republik (= Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft 196). Göttingen 2011.