Magazines with Caricatures

by Jecheskiel David Kirszenbaum

Magazines with Caricatures by Jecheskiel David Kirszenbaum

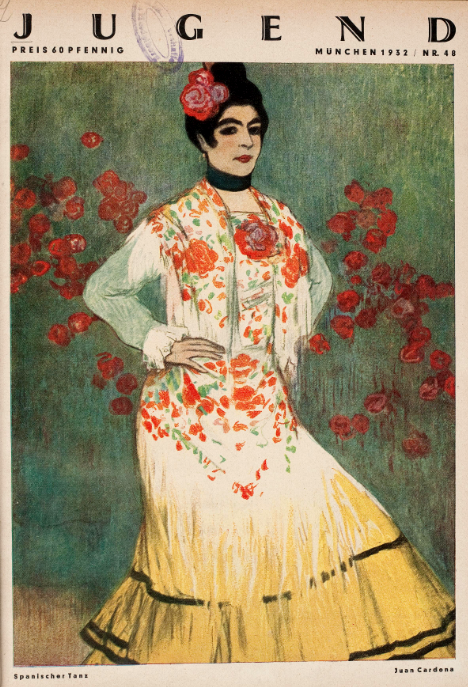

Jugend – Münchner illustrierte Wochenschrift für Kunst und Leben

(Youth – Munich Illustrated Weekly for Art and Life)

The Jugend – Münchner illustrierte Wochenschrift für Kunst und Leben (Youth – Munich Illustrated Weekly for Art and Life) was published by Georg Hirt (1841–1916) as a magazine committed to the Art Nouveau style of both art and literature. In the 1920s, the journal initially had problems adapting to the new art movements; however, contributions from artists such as Georg Grosz (1893–1959) and Jecheskiel David Kirszenbaum and texts by Kurt Tucholsky (1890–1935) and Erich Kästner (1899–1974) helped it regain the interest of readers. After 1933, its attempt to adapt to the understanding of art dictated by national socialism failed. Jugend ceased publication in 1940 due to a lack of readers.

Juan Cardona Llados (1877–1957): Spanish dance

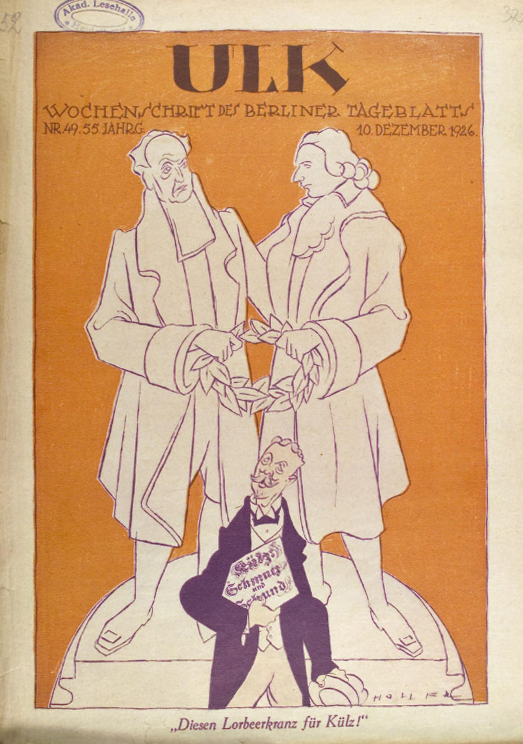

ULK – Illustriertes Wochenblatt für Humor und Satire

(Illustrated Weekly Journal for Humor and Satire)

ULK stands for “Unsinn – Leichtsinn – Kneipsinn” (Nonsense, Carelessness, Trickery). The Berlin publishers Rudolf Mosse (1843–1920) and Siegmund Haber (1835–1895) embraced this objective when they named the magazine ULK. Illustriertes Wochenblatt für Humor und Satire. It was conceived as a Prussian counterpart to Fliegende Blätter (Flying Letters), a satirical weekly which has published in Munich since 1845. The ULK regularly commented on current political and social issues, appearing every Thursday as a free supplement to the Berliner Tagblatt and, from 1910, also to the Berliner Volks-Zeitung. From 1922, the ULK appeared as an independent publication. After the bankruptcy of the Berliner Tagblatt in 1932, the ULK ceased publication.

Kurt Tucholsky (1890–1935) worked as editor-in-chief of ULK from 1918 to 1920, also publishing his own articles under the pseudonyms Kaspar Hauser, Peter Panter, Theobald Tiger and Ignaz Wrobel. In addition to Jecheskiel David Kirszenbaum, Heinrich Zille (1858–1929), Georg Grosz (1893–1959), and Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) worked

for the magazine as artists.

In the midst of the heated discussions about a law of designed to protect youth from “trashy and dirty writings,” which was understood by some as censorship, the cover of the ULK of December 10, 1926 showed Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Külz (1875–1946) being presented a laurel wreath by Goethe and Schiller. The law was enacted on December 18, 1926.

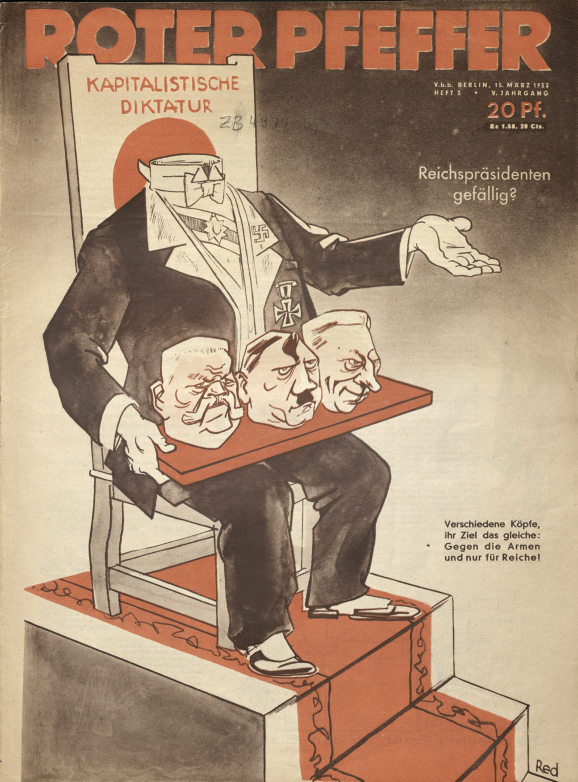

Roter Pfeffer (Red pepper)

The magazine Roter Pfeffer was in circulation from 1932 until its ban in February 1933. Its publication was intended to be a communist response to bourgeois press groups such as Der Querschnitt, ULK, and Simplicissimus.

The front page of the issue covering the 1932 Election of the Reich shows from left to right the heads of Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) and Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia (1882–1951), whose candidacy had also been considered by the DNVP, but which ultimately failed due to the ban by the former Kaiser Wilhelm II.

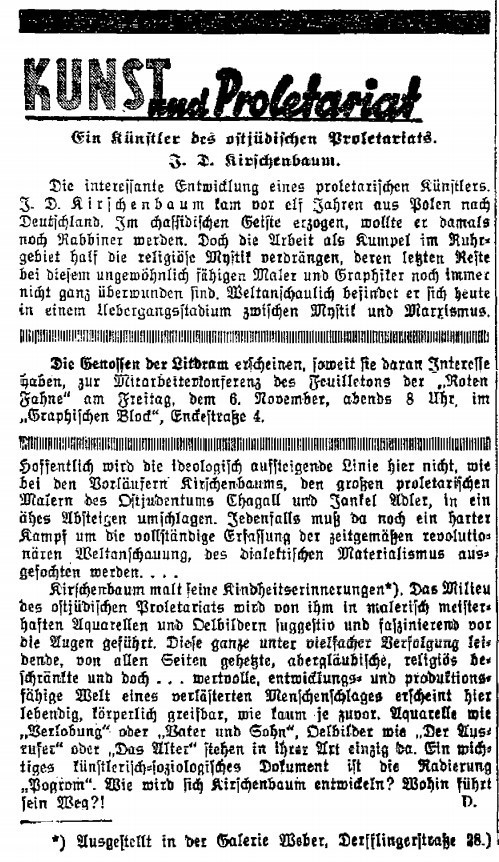

Die Rote Fahne (the red banner)

Die Rote Fahne was founded on November 9, 1918 as a newspaper of the Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). On January 1, 1919, it became the central press organ of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Among its first editors were Karl Liebknecht (1871–1919) and Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919). After the newspaper was banned by the Nazi regime in 1933, the newspaper kept producing copies abroad until the beginning of the war in 1939. Helen Ernst (1904–1948), George Grosz (1893–1959), and John Heartfield (1891–1968) designed graphics and caricatures alongside Kirszenbaum. Not many of the caricatures are signed, which makes it difficult to attribute them to the individual artists. This measure presumably served to protect the caricaturists from possible attacks by political opponents.

The review of Kirszenbaum’s works by the cultural editor and art critic Alfred Durus (pseudonym of Alfréd Kemény, 1895–1945) in the November 5, 1931, edition of the Red Flag placed the artist ideologically in a “transitional state between [Jewish] mysticism and Marxism.”

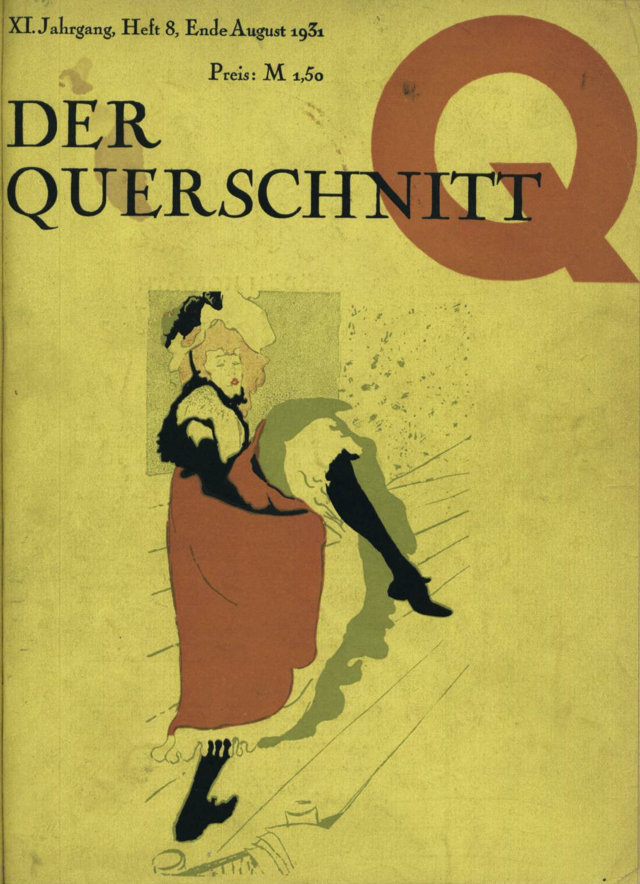

Der Querschnitt

Der Querschnitt was founded in 1921 by the art dealer Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937), initially as a newsletter for his galleries in Düsseldorf and Berlin. After 1924 it was published by Hermann Ullstein (1875–1943) as a magazine in the Propyläen Publishing House. The publication featured reports on modern art and literature and targeted a more elitist audience. Der Querschnitt had an ironic undertone but was largely politically neutral.

The global economic crisis of 1929 and the Nazi’s rise to power in 1933 caused considerable declines in circulation, especially since all the well- known copywriters and graphic artists had gone into exile. The Ullstein family publishing company was “Aryanized” in 1934. Edmund Franz von Gordon (1901–1986) tried to continue publishing the paper despite political constraints; however, when he published a satirical “Foreign Dictionary” in September 1936, in which the term “absurd” was defined as “someone still hoping for better times,” the magazine was banned by Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945), the Nazi Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901): Lithograph based on his poster of the revue dancer Jane Avril (1868–1943), 1892

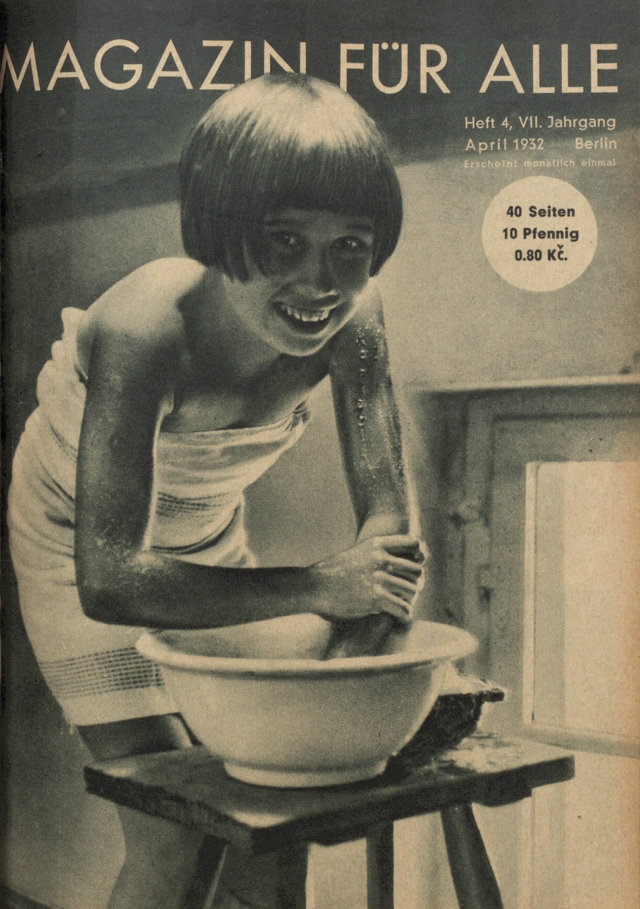

Magazin für alle

In October 1926, Willi Münzenberg (1889–1940) founded the publishing house Universum Bücherei für alle G.m.b.H. as a communist book community on behalf of the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe (IAH), alongside the Bücherkreis der Sozialdemokratie and the trade union Büchergilde Gutenberg. As a monthly gift to members, the magazine Blätter für Alle was published, which was later renamed Magazin für Alle. In total, 132,000 copies of the magazine were circulated. In Germany, after the National Socialists came to power in 1933, all printed matter published by the IHA was banned.

Laurence Danguy: L’ange de la jeunesse. La revue Jugend et le Jugendstil à Munich. Paris 2009.

Dietrich Grünewald: Studien zur Literaturdidaktik als Wissenschaft literarischer Vermittlungsprozesse in Theorie und Praxis. Zur didaktischen Relevanz von Satire und Karikatur. Verdeutlicht an der satirischen Zeitschrift Eulenspiegel/Roter Pfeffer 1928–1933. Gießen 1976.

Wilmont Haacke und Alexander von Baeyer (Hg.): Der Querschnitt – Facsimile Querschnitt durch den Querschnitt 1921–1936. Frankfurt/M 1977.

Ursula E. Koch: Der Teufel in Berlin. Von der Märzrevolution bis zu Bismarcks Entlassung. Illustrierte politische Witzblätter einer Metropole 1848–1890, Köln 1991.

Stephan Steins: Zur Geschichte der Roten Fahne 9. November 1918 – 2018. 100 Jahre Die Rote Fahne. In: Die Rote Fahne. Sozialistisches Magazin. 2018 https://rotefahne.eu/Geschichte/#2000-2003.