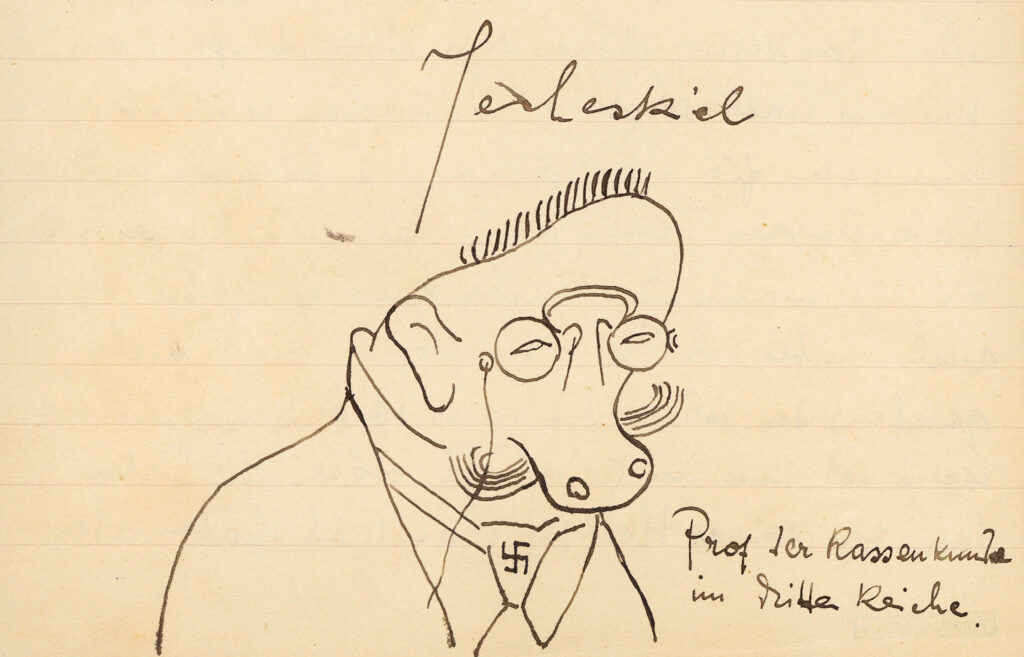

Professor of Race Studies

In a letter written on April 23, 1934 from Paris, Kirszenbaum sketches a caricature of an anonymous Professor of Racial Studies in the Third Reich. It is possible he was thinking of Hans F. K. Günther (1891–1968), whose book “Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes” appeared in 1922.

Professor of Race Studies

In a letter written on April 23, 1934 from Paris, Kirszenbaum sketches a caricature of an anonymous Professor of Racial Studies in the Third Reich. It is possible he was thinking of Hans F. K. Günther (1891–1968), whose book “Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes” appeared in 1922.

In 1930, as ordered by Dr. Wilhelm Frick, Thuringia’s Minister of the Interior and National Education and a member of the NSDAP, a chair of social anthropology was established at the University of Jena for the so-called “Rassegünther”. On September 15, 1935, the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor were passed. Both were commissioned by Frick, who has become Reich Minister of the Interior. These Nuremberg laws degraded German citizens of Jewish descent to people of lesser rights.

Professor of Racial Studies in the Third Reich

Kirszenbaum attached this caricature of a National Socialist “professor of racial studies” to a report on picture sales in Paris.

Hans F. K. Günther (1891 – 1968)

Hitler, who suggested the establishment of a chair for “race issues and racial studies,” attended Günther’s inaugural lecture in Jena together with Hermann Göring. From 1935 Günther was a full professor of racial studies, peoples’ biology and rural sociology at the University of Berlin. During his denazification proceedings he was initially classified as “Minderbelasteter,” but after an appeal process in 1951 he was downgraded to “Mitläufer.”

The American Society of Human Genetics elected him a corresponding member in 1953.

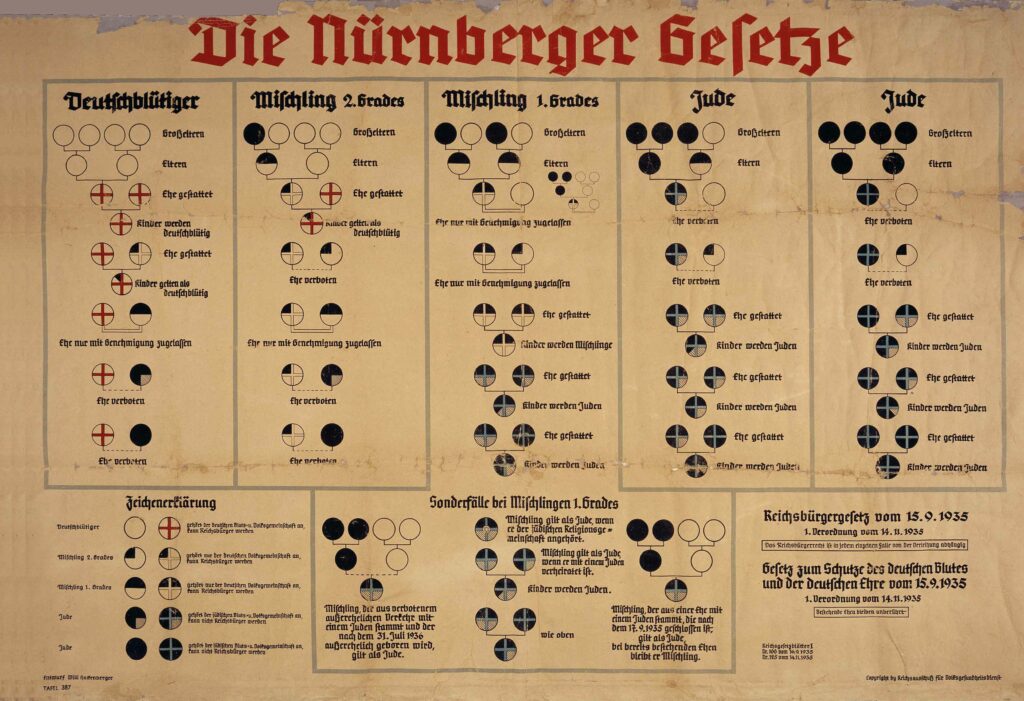

The Nürnberg Laws

This table explains the Nürnberg Laws of September 15, 1935 and the Ordinance of November 14, 1935.

The Nürnberg Laws established a pseudo-scientific basis for the identification of “races.” Only people with four non-Jewish German grandparents (four white circles in the top row on the left) were of “German blood.” A Jew was defined by the Nazis as someone who was descended from three or four Jewish grandparents (black circles in the top row on the right). In the middle were people with “mixed blood” of the “first or second degree. A Jewish

grandparent was defined as a person who had ever been a member of a Jewish religious community. Also included is a list of permitted marriages and prohibited marriages.

Worldviews and Dilettantism

In 1928, the Berlin pedagogue Dr. Kurt Lewin published a review of Günter’s dilettante work. “Only the dilettante can present such uncertain things with such convincing certainty that the masses take notice and – if there is only method in the nonsense – build a worldview out of the content because it appeals to them.”

The review appeared in the Central-Vereins- Zeitung, Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum, and Organ des Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens. The C.V.– Zeitung was printed by Rudolf Mosse, who also published the ULK, for which Duwdiwani drew caricature.

Cornelia Essner: Die »Nürnberger Gesetze« oder Die Verwaltung des Rassenwahns 1933–1945. Paderborn 2002.

Volker Koop: Wer Jude ist, bestimme ich. »Ehrenarier« im Nationalsozialismus. Köln/Weimar/Wien 2014.

Elvira Weisenburger: Hans Friedrich Karl Günther, Professor für Rassenkunde. In: Michael Kißener / Joachim Scholtyseck (Hg.): Die Führer der Provinz. NS-Biographien aus Baden und Württemberg (= Karlsruher Beiträge zur Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus 2). Konstanz 1997, S. 161–199.