The Triumph of Boxing

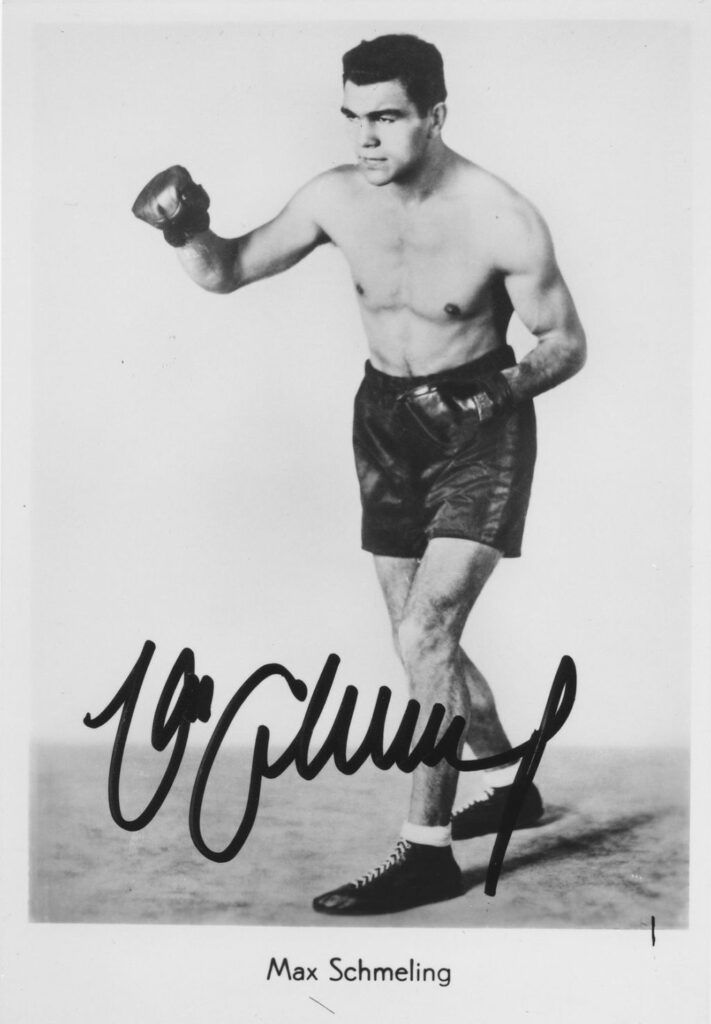

Boxing, cycling, and soccer all became mass phenomena during the Weimar Republic. The first German boxing championships were held in 1920, after which the Republic experienced a “Boxing boom”. Max Schmeling (1905–2005), the European champion in 1927 and 1939 and world champion in 1930 and 1931, became a German national hero. Fights became hugely popular and profitable sporting events.

The Triumph of Boxing

Boxing, cycling, and soccer all became mass phenomena during the Weimar Republic. The first German boxing championships were held in 1920, after which the Republic experienced a “Boxing boom”. Max Schmeling (1905–2005), the European champion in 1927 and 1939 and world champion in 1930 and 1931, became a German national hero. Fights became hugely popular and profitable sporting events.

Max Schmeling

In 1934, a fight between Schmeling and Walter Neusel (1904–1964) in Hamburg was attended by about 100,000 spectators. This is still the largest number of spectators ever recorded at a boxing event in Europe.

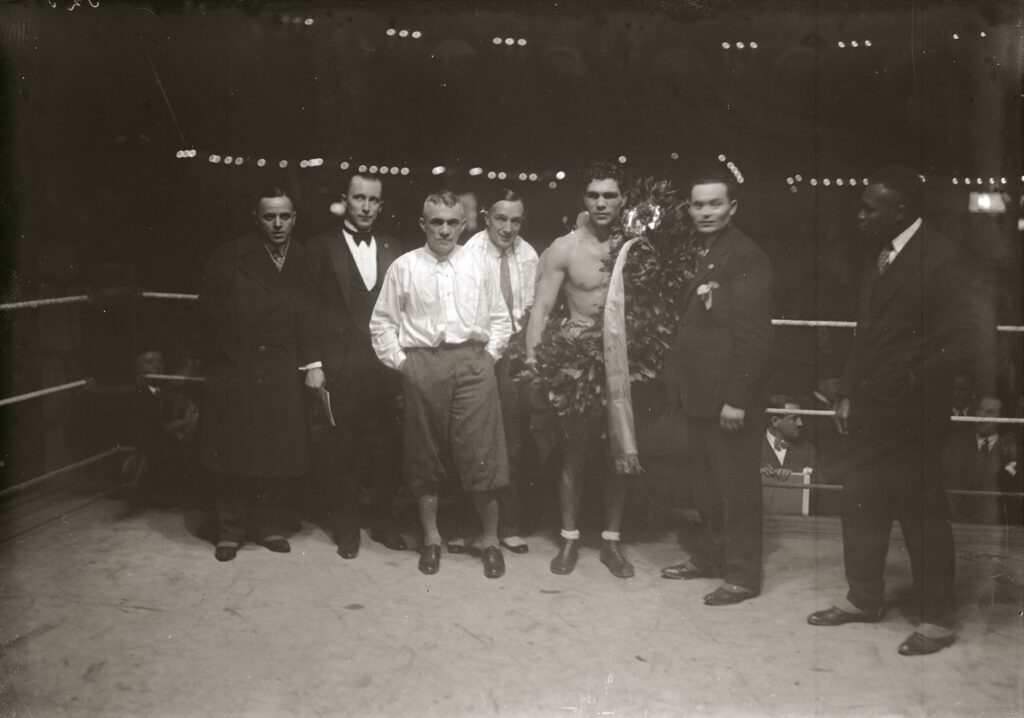

K.o. in the first round

European light heavyweight boxing champion Max Schmeling (1905–2005) with the victory wreath after knocking out Italian champion Michele Bonaglia (1905–1944) in the first round of a match in front of tens of thousands of spectators at the Berlin Sports Palace on January 6, 1928.

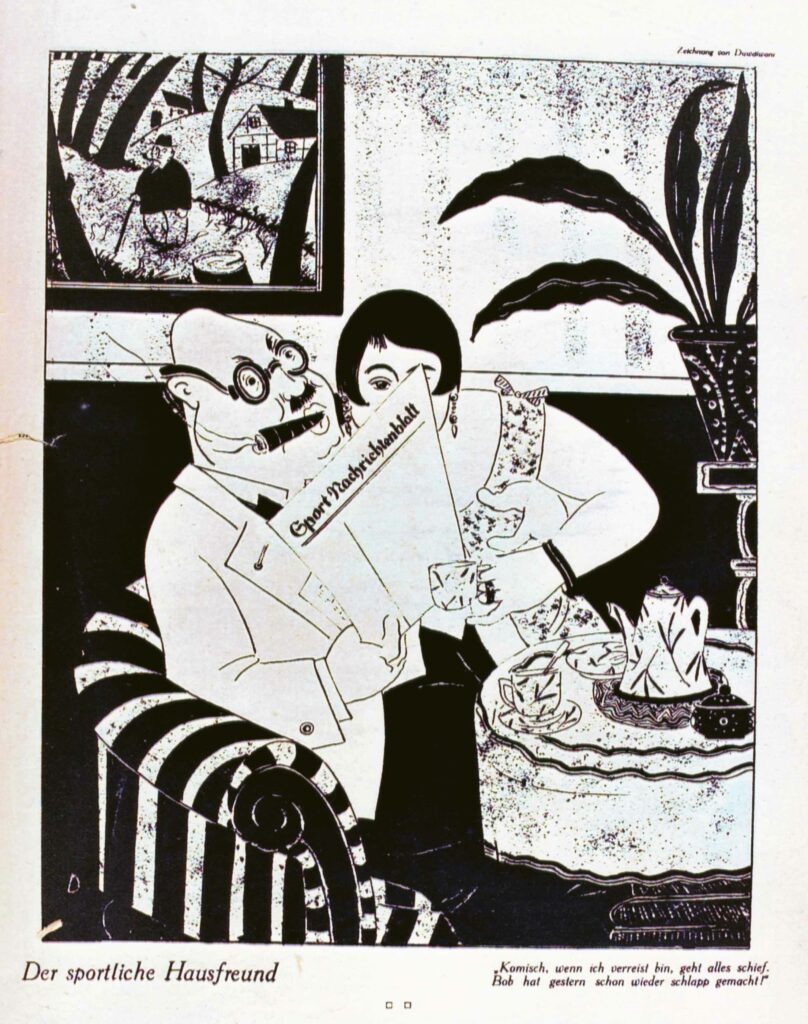

The Athletic House Friend

“Funny, once I go on a trip, everything goes wrong. Bob went limp again yesterday!”

The dictionary defines the term “house friend”as the lover of a married woman. The obese gentleman on the sofa is a cuckold whose main sporting activity is probably reading the sports news. The “housefriend” referenced in the title, presumably named Bob, is absent from this image. It seems Bob’s sexual exploits were a detriment to his athletic performance.

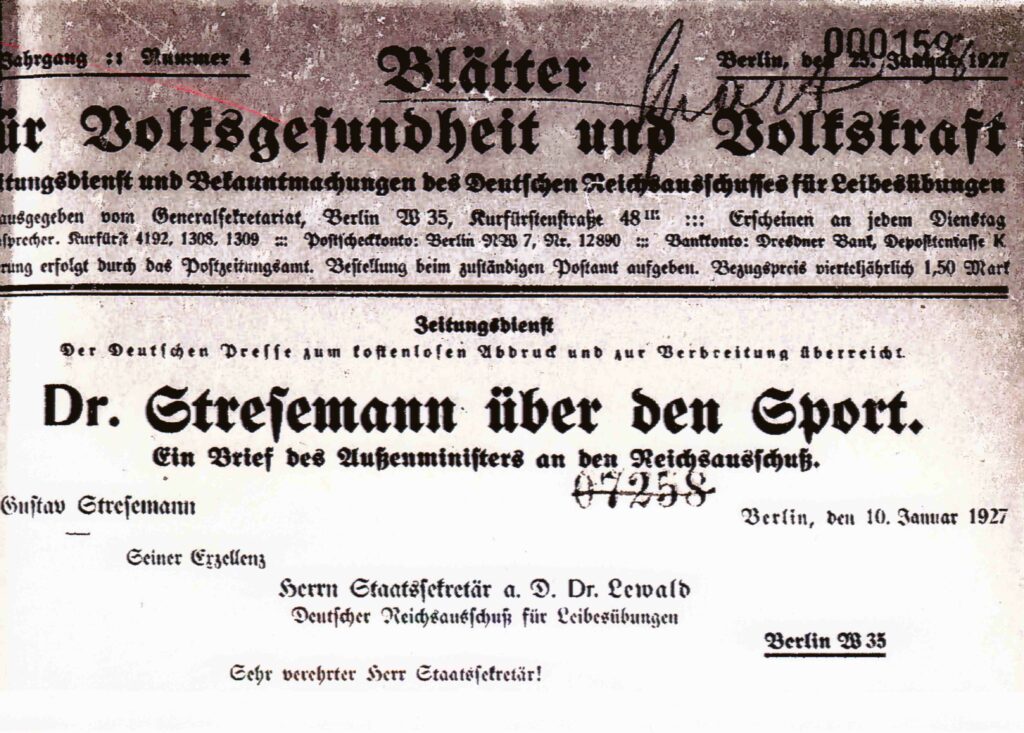

The commercialization of sport and the elevation of athletes to national heroes was not a popular development for everyone. Reich Foreign Minister Dr. Gustav Stresemann (1878–1929) repeatedly rejected competitive sports in speeches and newspaper articles, arguing that a “professional sports system” had turned “physical training” into a major media event. This, he claimed, led to addiction and physical damage. In contrast, Stresemann explicitly spoke out in favor of any form of popular sport and physical training, including hiking.

Professional Sports vs. Physical Training

Open letter from Dr. Gustav Stresemann to the German Reich Committee for Physical Education on Popular and Competitive Sports, January 10, 1927.

Foto: Max Schmeling 1938, Sammlung New York World-Telegram and Sun der Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Christiane Eisenberg: Massensport in der Weimarer Republik. In: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 33/1993, S. 137–178.

Knud Kohr / Martin Krauß: Kampftage – Die Geschichte des deutschen Berufsboxens. Göttingen 2000.

Martin Krauß: Schmeling. Die Karriere eines Jahrhundertdeutschen. Göttingen 2005.

David Pfeifer: Schmeling, Max. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie 23 (2007), S. 125–126.

Karin Rase: Kunst und Sport. Der Boxsport als Spiegelbild gesellschaftlicher Verhältnisse. Frankfurt a. M. 2003.

Swantje Scharenberg: Die Konstruktion des öffentlichen Sports und seiner Helden in der Tagespresse der Weimarer Republik. Karlsruhe 2006.

Bernd Wedemeyer-Kolwe: »Der neue Mensch«. Körperkultur im Kaiserreich und in der Weimarer Republik. Würzburg 2004.